Randomized control trial

Sujit Kumar Tripathy

Asst Professor, Dept of Orthopaedics

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar

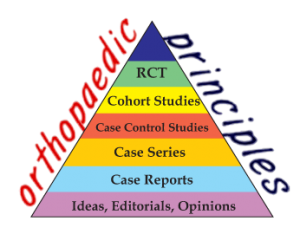

A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is a specific type of scientific experiment, and it is considered as the gold standard for a clinical trial. These trails are often conducted to evaluate the efficacy and/or effectiveness of various types of medical intervention within a patient population. Also it may be used in providing useful information about adverse effects, such as drug reactions.

Definition: RCTs are studies that measure an intervention’s effect by randomly assigning individuals (or groups of individuals) to an intervention group or a control group.

For example, suppose that a scientist wants to know about a new surgical technique which he believes to be more effective than the existing technique for treatment of osteonecrosis of femoral head. Then he has to undertake an RCT which randomly assigns osteonecrotic patients to either a trial group, who will be treated with the new surgical technique, or to a control group, who will be treated with the conventional surgical technique. The RCT would then measure outcomes – such as improvement in radiology (MRI) and hip function (Harris hip score) – for both groups over a period of time. The difference in outcomes between the two groups would represent the effect of the new surgical technique compared to the conventional technique.

Methods of randomization:

Four common method of randomization used in clinical practice are,

- Completely randomized: assign subjects to treatments at random

- Randomized block: group subjects who are similar into “blocks”; then assign subjects to treatments in each block

- Matched pair: form pairs of subjects to be as similar as possible; then assign one in each pair to each treatment

- Repeated measures: give every treatment to each subject

Classifications of RCTs

a)As per study design:

- Parallel-group: each of the participants of the study is randomly assigned to a group, and all the participants in the group receive (or do not receive) an intervention.

- Crossover: over time, each participant receives (or does not receive) an intervention in a random sequence.

- Cluster: pre-existing groups of participants (e.g., villages, schools) are randomly selected to receive (or not receive) an intervention.

- Factorial: Each participant is randomly assigned to a group that receives a particular combination of interventions or non-interventions (e.g., group 1 receives drug A and drug B, group 2 receives drug A and placebo B, group 3 receives drug A and drug B, and group 4 receives drug A and drug B).

b) By outcome of interest (efficacy vs. effectiveness)

- Explanatory RCTs test efficacy in a research setting with highly selected participants and under highly controlled conditions

- Pragmatic RCTs test effectiveness in everyday practice with relatively unselected participants and under flexible conditions; in this way, pragmatic RCTs can “inform decisions about practice.

c) By hypothesis (superiority vs. noninferiority vs. equivalence)

The classification of RCTs as “superiority trials,” “noninferiority trials,” and “equivalence trials,” differ in methodology and reporting.

- Majority of RCTs are superiority trials, in which one intervention is hypothesized to be superior to another in a statistically significant way.

- Noninferiority trials: to determine whether a new treatment is no worse than a reference treatment

- Equivalence trials: the hypothesis is that two interventions are indistinguishable from each other

Common problem in any experimental studies and methods to avoid them in RCTs:

There are four common problems in experimental studies:

1. Confounding variables

2. Interactions

3. Placebo, Hawthorne and experimenter effects

4. Ecological validity and generalizability

Confounding variables: A confounding variable is related both to the explanatory variable and the response. If present, it could distort the results of the experiment.

How it can be avoided in RCT?- By Randomization this problem can be easily solved. If you assign subjects to treatments at random, then there will be no systematic differences between the groups (only random differences), and confounding will be eliminated.

Example: Osteonecrotic patients treated with core decompression showed better radiological and functional outcome than patients managed conservatively.

As the treatment was self selected there are many variables. Patients treated with core decompression and managed conservatively could have differed in many aspects: age, sex, etiology, stage of the disease etc, these variables can explain the difference between both the groups.

Solution: Randomize both the groups so that both the groups will be comparable.

Interactions

Interaction means that the effect of an explanatory variable on a response differs across groups. If this interaction is not reported, the overall results could be misleading. If you find a relationship between two variables, check to see if that relationship holds across groups.

Placebo, Hawthorne and experimenter effects

All three of these phenomena are related to the power of suggestion.

Placebo effect: Subjects may show improvement even when given a treatment that has no active ingredients.

Hawthorne effect: Subjects may change their behavior because they know they are being watched or studied.

Experimenter effect: Bias that creeps into a study because the researchers expect or hope for a particular result.

What to do avoid them?-Hawthorne effects can be reduced by making the measurement process less obvious or less obtrusive. Placebo and experimenter effects can be reduced by making the study double blind. Note: Placebo and experimenter effects may still creep into a double-blind study, because the blinding might not be completely effective.

Ecological validity and generalizability

These pertain to how well the results of an experiment may hold up “in the real world”.If the study takes place in a laboratory rather than in the subjects’ natural environments, it may lack ecological validity. If the study subjects come from an atypical or unusual segment of the population, the results may not hold for the greater population.

Solution: Wherever possible, use subjects who are typical of the population and study them in their natural settings.

Key issues in designing a randomized trial:

- Randomisation : How will patients be randomised to the different interventions?

- Sample size calculation: What will inform the sample size calculation, in particular, what clinical difference is being sought to be identified?

- Inclusion & exclusion criteria: The inclusion and exclusion criteria should be sufficiently specific so as to ensure that appropriate participants are invited to consent to take part in the trial. However, it should not be so specific that the participant sample becomes too far removed from the population to which you wish to apply the results.

- Recruitment schedule:The recruitment schedule should identify from where the potential participants will be sought along with some indication of the likely time required to recruit the required sample size.

- Primary and secondary outcomes:The primary and secondary outcomes should be clearly identified. Outcomes should be selected that are highly appropriate to the issue being investigated and which can be measured in a valid and reliable manner. Ideally, blinded outcome assessment should be achieved.

- Patient follow up plan: Missing data can scupper the best designed study. Therefore, thought should be given to how data will be collected and plans should be made to minimise the risk of missing data.

- Analysis plan: The analysis plan should clearly state how missing data will be managed and what statistical approaches will be applied. Ideally an intention to treat analysis should be adopted.

Advantages of Randomization:

It enables to assess whether the intervention itself, as opposed to other factors, causes the observed outcomes. Specifically, randomly assigning a sufficiently large number of individuals into either an intervention group or a control group ensures, to a high degree of confidence, that there are no systematic differences between the groups in any characteristics (observed and unobserved) except one – namely, the intervention group participates in the intervention, and the control group does not. Therefore, assuming the RCT is properly carried out, the resulting difference in outcomes between the two groups can confidently be attributed to the intervention and not to other factors. The randomisation process greatly reduces the risk of bias.

Disadvantages of randomization:

RCTs are expensive and time taking. RCT’s external validity may be limited, that means application of the result of RCT on a general population may be limited. It may be affected by conflict of interest and cultural effects. It may not be feasible always to conduct RCT due to study participants’ concerns about random assignment. Well-matched comparison-group designs may be a good alternative when an RCT is not feasible.

References:

- 1. Random Controlled Trials (RCTs). https://www.azed.gov/wp content/uploads/PDF/RCT.pdf

- Sibbald B, Roland M. Understanding controlled trials: Why are randomised controlled trials important? BMJ 1998;316:201

For more Reviews,

http://orthopaedicprinciples.com/my-books/orthopaedic-principles-a-review/

Leave a Reply